, Synchronised two-channel projection, configurable screens, sand from Macassar Dunes, and costumes, 16’54 min.jpg)

Kammakamma

2022 - 2024

4K video, Synchronised two-channel projection, configurable screens, sandbags with sand from Macassar Dunes, props and costumes

First episode of iterative work

16’54 min

Cast in order of appearance

Hen: Ben Albertyn

Aunty B-Sierra: Ibtisaam Florence

Makassarese Nobel-Branton: Cole Wessels

Matriekafskeid-Ronelda-Doppelganger-Ronelda: René Cloete

Screenplay, cinematography, costumes & editing

Abri de Swardt

Translation

Annel Pieterse

Translations

Natasja Schellaars-le Roux (Dutch), and Fanjatiana Manitrinirainy Rabemiafara (Malagasy)

Cinematography

Wihann Strauss

Sound Recording

M.S. Retief

Mixing

Dawid de Villiers

Installation view Kammakamma POOL x Field Station, Green Point Park, Cape Town, 1 February - 3 March 2024

, Synchronised two-channel projection, configurable screens, sand from Macassar Dunes, and costumes, 16’54 min.jpg)

Kammakamma

2022 - 2024

4K video, Synchronised two-channel projection, configurable screens, sandbags with sand from Macassar Dunes, props and costumes

First episode of iterative work

16’54 min

If the river’s mouth could speak, what would it say? Enacting the possibility of river mouths as storytellers and historiographers, Kammakamma is the opening episode of the second work in a moving-image trilogy that visually, archivally and sonically explores the Eerste River in South Africa as witness and carrier of submerged narratives. The Eerste River’s nomenclature derives from Simon van der Stel, the Dutch East India Company (VOC) colonial governor who in 1679 annexed land for settler agriculture at the first (Dutch, ‘eerste’) river he encountered after Cape Town, over time erasing the names the river had in indigenous tongues. Structured in an iterative unfolding towards feature length, Kammakamma (2022 – 24) is a synchronised two-channel video projection which transpires along the river through three geographically, temporally and affectively distinct yet interconnected chronicles written by De Swardt, poet and novelist Ronelda S. Kamfer, and historian Saarah Jappie. Its title draws from slippages between the Khoekhoe language terms for water (‘//amma’) and similitude (‘khama’), with ‘kamma’ absorbed into Afrikaans to mean ‘make believe’. Through this interplay, Kammakamma considers the river as a source of shifting stories, and as a saturation point for understanding the effects of climate and catastrophe.

In the opening episode of Kammakamma De Swardt probes one of the founding myths of Afrikanerdom through the figure of Hendrik Biebouw, a teenage idler. Biebouw, alongside three others attacked a VOC watermill attached to the Eerste River in 1707, during which, in an altercation with the interceding Stellenbosch village magistrate, Johannes Starrenburg, Biebouw infamously asserted himself, imbibed, as an “Africaander”. At the time this term was solely attributed to enslaved, manumitted, or indigenous peoples at the Cape, a fact often sanitised from interpretations of the event, meaning Biebouw’s utterance was a transposition. Starrenburg duly recorded the insurgency; by the subsequent census Biebouw is registered as ‘Gone’. For De Swardt Biebouw’s declaration not only is inextricable from the river where it was spoken – haunting its flow – but also from the substance of wine as settler-colonial agent, and from the instability of language itself. Portrayed by the actor and art writer Ben Albertyn, Biebouw is speculatively recast in a purgatorial state sifting sand from sandbags mined around the river mouth from the dunes in Macassar back into the river at the blocked confluence of the Eerste and Plankenbrug Rivers on the periphery of Stellenbosch. Working through notions of watery personification and possession, Biebouw is presented as a fractured, excessive subject contradicting and complicating his own tale of class rebellion, a ghost wading in a feedback loop. Approximating the river, he seeks confluence, feverishly putting forward inundating and porous acts.

Developed through De Swardt's sonic technique of ‘sunstrokes of voice’ – dense and delirious forms of speech which incapacitate the articulating subject – Biebouw’s vocalisations in Kammakamma invert figures of speech and conjoin words, jumbling Afrikaans, Dutch, German and Malagasy. Interludes filmed in the wake of flooding show the river as subjected to disaster management and hydro-engineering, as an entrancingly wild and man-made entity. Tableaux drawing from swimming and life-saving manuals introduce the whole ensemble, with the actors René Cloete, Ibtisaam Florence, and Cole Wessels playing protagonists in following episodes, while demonstrating the suffocating, burdensome effects the instrumentalisation of Biebouw’s words continue to have. Through the form of synchronised two-channel projection, De Swardt plays upon the idea of ‘seeing double’, of states of intoxication and parallel temporalities, but more troublingly of perception itself as disorientation.

, Synchronised two-channel projection, configurable screens, sand from Macassar Dunes, and costumes, 16’54 min 2_v2.jpg)

, Synchronised two-channel projection, configurable screens, sand from Macassar Dunes, and costumes, 16’54 min 2a.jpg)

Kammakamma

2022 - 2024

4K video, Synchronised two-channel projection, configurable screens, sandbags with sand from Macassar Dunes, props and costumes

First episode of iterative work

16’54 min

Installation views Kammakamma POOL x Field Station, Green Point Park, Cape Town, 1 February - 3 March 2024

, Synchronised two-channel projection, configurable screens, sand from Macassar Dunes, and costumes, 16’54 min 3.jpg)

, Synchronised two-channel projection, configurable screens, sand from Macassar Dunes, and costumes, 16’54 min 4.jpg)

, Synchronised two-channel projection, configurable screens, sand from Macassar Dunes, and costumes, 16’54 min 6.jpg)

, Synchronised two-channel projection, configurable screens, sand from Macassar Dunes, and costumes, 16’54 min 7.jpg)

, Synchronised two-channel projection, configurable screens, sand from Macassar Dunes, and costumes, 16’54 min 8.jpg)

, Synchronised two-channel projection, configurable screens, sand from Macassar Dunes, and costumes, 16’54 min 9.jpg)

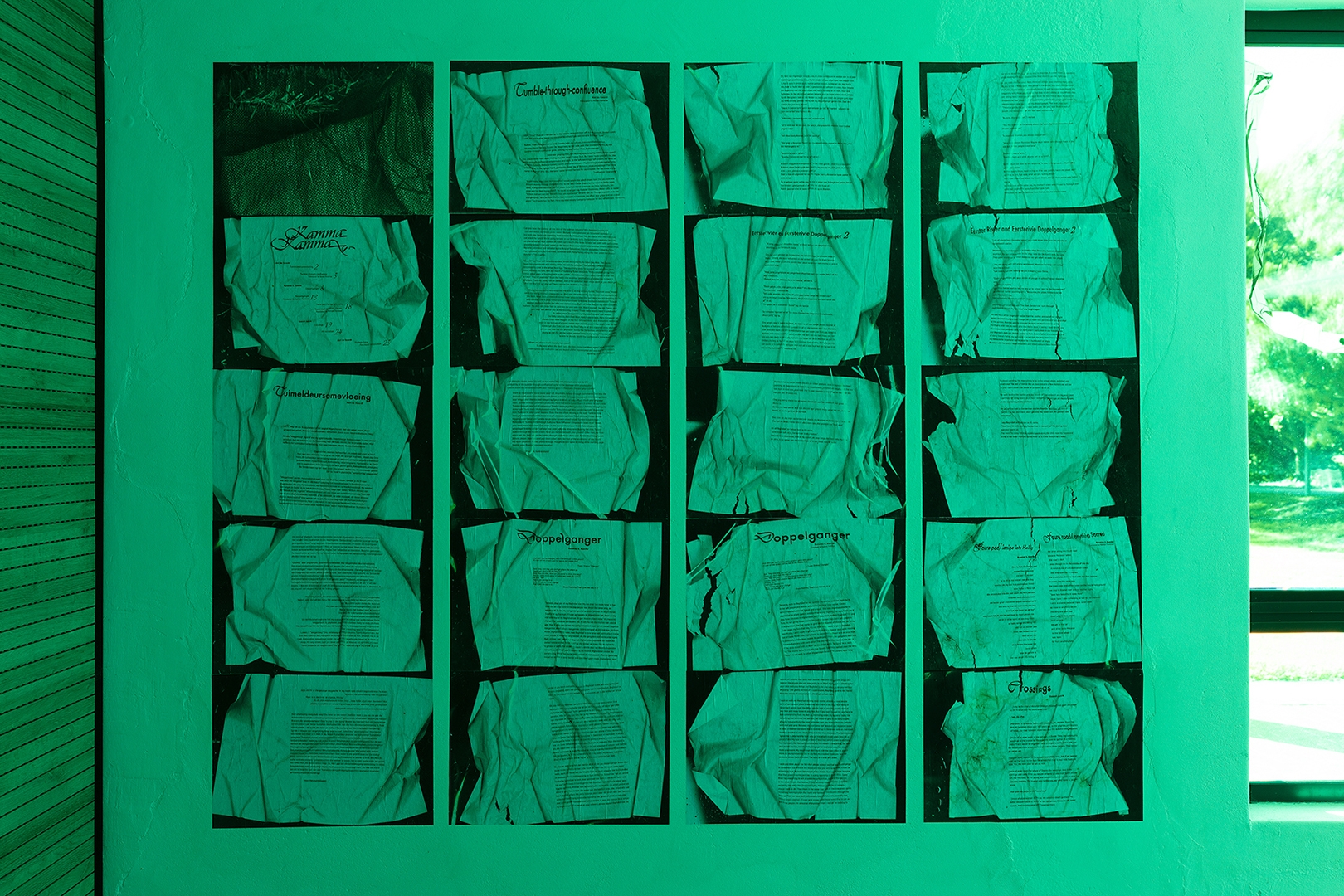

Kammakamma

2024

E-publication, QR-code, paper, wheat-paste, 32 pages

Dimensions variable

Texts

Abri de Swardt Tuimeldeursamevloeing

translated by Annel Pieterse as Tumble-through-confluence

Ronelda S. Kamfer Doppelganger

translated by Nathan Trantraal

Ronelda S. Kamfer Faure pad /ienige iets Heilig

translated by Nathan Trantraal as Faure road/ anything Sacred

Saarah Jappie Crossings

with translations by Jappie (Bahasa Indonesia), Muhammad Setiawan, Muhammad Zuhairi Abdullah, and Marlina Mansyur (Makassarese)

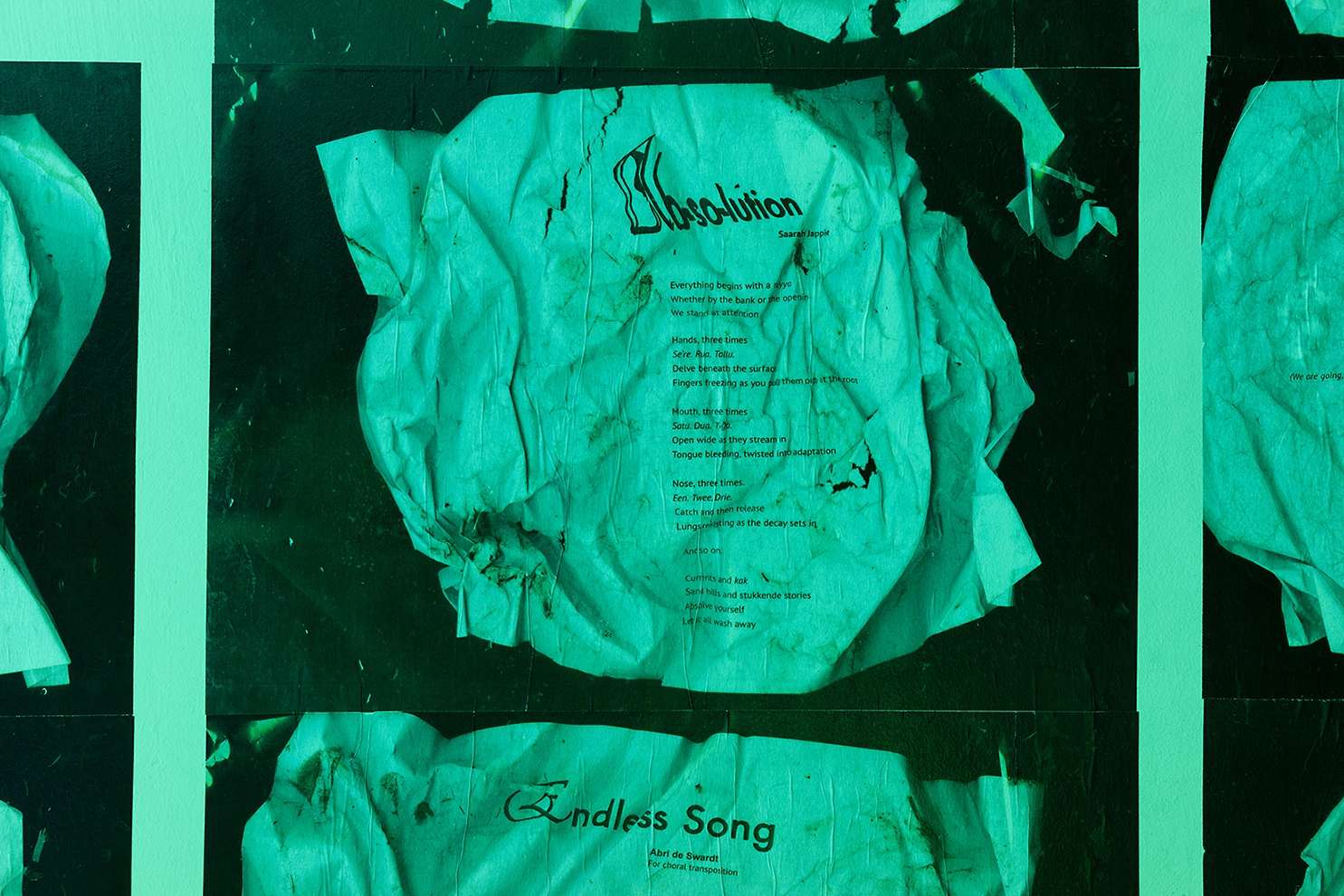

Saarah Jappie Ab-so-lution

Abri de Swardt Endless Song

Design Heléne van Aswegen

Installation view Kammakamma, POOL x Field Station, Green Point Park, Cape Town, 1 February - 3 March 2024

An accompanying e-publication, displayed as a wheat-paste, presents the screenplay of Kammakamma in its entirety, moving episodically from confluence to mouth. Kamfer’s texts, written in Kaaps, use auto-fiction to navigate nuances of disassociation and code-switching. Through the character of Ronelda, a late ‘90s teenager and one of many doppelgangers, the narrative moves between Eersterivier, Faure and Stellenbosch, in an odyssey of everyday pleasures amid illusory systemic change. Jappie’s writing approaches the sacred burial site, or kramat, of the repatriated 17th-century Eastern Indonesian exile and Islamic anticolonial leader, Sheikh Yusuf of Makassar, next to the river at Macassar, through intergenerational, infrastructural, and transoceanic lenses. Elements of memorialisation, pilgrimage, and caretaking arise to counter limiting archival inscriptions, and to illuminate traces of the natural environment intertwined with diverse, lived experiences of this spiritual landscape. The publication concludes in an eco-horror chorus for the convergence of oceanic, fluvial and sewage waters at the mouth. As a collection, the publication entangles various scales and positions, seeking to re-imagine relations between the river and the racially, spatially and economically divided communities along its trajectory by insisting upon the potential of the river as a commons.

, Prop from future iteration of Kammakamma and wine, installation view Kammakamma, POOL, Cape Town new_v2.jpg)

Endless Song

2023

Prop from future iteration of Kammakamma, red wine

Dimensions variable

Installation view Kammakamma, POOL x Field Station, Green Point Park, Cape Town, 1 February - 3 March 2024

, Prop from future iteration of Kammakamma and wine, installation view Kammakamma, POOL, Cape Town 2 new.jpg)

Endless Song, an architectural model of the Stellenbosch Moederkerk Dutch Reformed Church made from boxed wine, alludes to the limitations of the doctrine of forgiveness when considering processes of land reform, national reconciliation, and reparations.

, Window film, packaging tape, collage 2 new.jpg)

Canal-Eyes-Canalise-Canal-Lies

2024

Window film, packaging tape, collage

Dimensions variable

Installation view Kammakamma, POOL x Field Station, Green Point Park, Cape Town, 1 February - 3 March 2024

, Window film, packaging tape, collage 4 new.jpg)

, Window film, packaging tape, collage 3 new.jpg)

, Installation view Spier Light Art 3 new.jpg)

Flood Light

2024

Steel, paint, LED-lights programmed on altering sequence, aircraft warning light, debris from the Eerste River, river sand

300 x 300 x 1200 cm

Steel Fabrication: ONSKANTOOR

Lights: BEKA-Schréder

Installation view Spier Light Art, Spier Wine Estate, 1 March - 1 April 2024

, Installation view Spier Light Art new.jpg)

Flood Light replicates a floodlight at the Danie Craven Rugby Fields next to the Eerste River at Stellenbosch University as if detached from its mast, toppled over, and washed up downstream through imagined severe flooding. Glitching and glowing both anxiously and mournfully, Flood Light speaks to the ecological state of the present while signalling our distraction from it.

Flood Light acts as a reminder of the ongoing extreme weather events made exponential, successive – and indeed anticipatory – during climate collapse, such as the region’s worst recorded flood in over forty-five years in 2023. Communities living along rivers are increasingly in precarious positions. Yet flooding events are inextricable from human encroachment upon the bodies of water they are dependent upon and which they alter in turn. From the onset of colonial settlement in the late 17th-century, the Dutch East India Company divided the alluvial flood plains along the entire span of the Eerste River into agricultural land, leading to hydraulic re-engineering like canalisation. Toni Morrison notes the word ‘flooding’ itself is an anthropocentric misattribution of a natural process. Rather than flooding, she writes that the river is “remembering”, “[r]emembering where it used to be”, as “water has a perfect memory and is forever trying to get back to where it was”. What arose from water, will again be submerged. Flood Light ultimately raises the prospect of the rewilding of the Eerste River.

, Installation view Spier Light Art 8 new.jpg)

, Installation view Spier Light Art 4 new.jpg)

, Installation view Spier Light Art 6 new.jpg)